BEER IS CHEAP! SEX IS FREE! WHAT HAPPENED TO THE CLASS OF ’73?

“AND SEAL THE DOOR WHERE EVIL DWELLS.” This line from Alice Bailey’s Great Invocation of 1945 came to mind as I walked around the twisted steel and rubble at Ground Zero of where the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, also in 1945. The bomb missed its intended target of a bridge and hit a hospital a few hundred meters away.

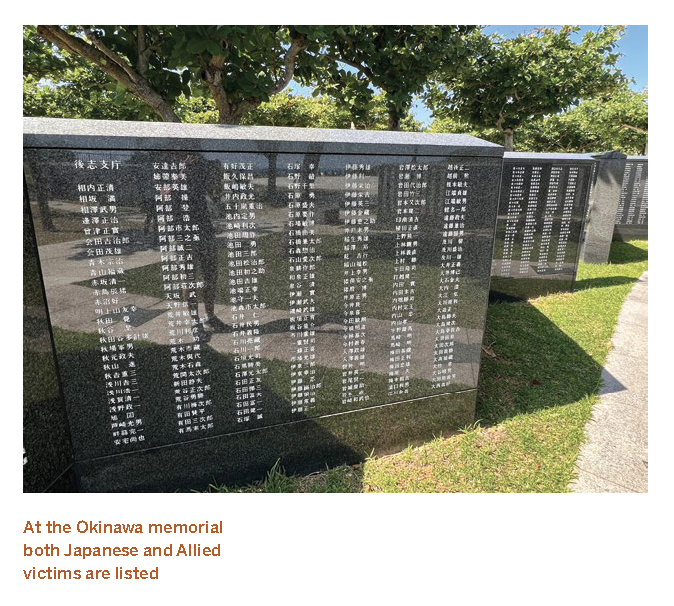

The line came to mind again in Okinawa, where a quarter of the civilians were killed not only by the allied war efforts but by the Japanese military that needed their resources. “Seal the door where evil dwells,”I thought as we toured a site where US soldiers, either with indifference or purpose, poured gasoline down a tunnel and dropped an incendiary into the shaft. The action was done without thought for a hungry, wet, and shivering girl who hid in a shallow nook, worried that the Japanese soldier nearby would steal her cat for food, rape her for comfort, and take her clothing for warmth. “Seal the door where evil dwells,” I thought. But where is the door? Really?

We headed next to Vietnam, and with the news blaring about Israel, Hamas, Ukraine, Ethiopia, Congo, China, and on and on, it was easy to think the world is just messed up; easy to say that it is not my problem or, with sadness, tell myself that I really do feel sorry for those people and go drink kombucha.

But what that journey really did was bring me back to my war and thinking about my recent 50th high school reunion. Does the world feel so messed up because of them—or because of us?

My class slogan—“Beer is cheap! Sex is free! We are the class of ’73!”—tells you what you need to know about our class. Vietnam was raging—we were watching the evils of war on TV and seeing older siblings, friends, and neighbors come back in body bags, strung out on drugs, or otherwise messed up from the evil they experienced.

We saw three options, none of them good:

Join: Give up our values and become part of a war we don’t believe in.

Join: Do horrendous things and come back strung out, feeling hopeless and guilty, unappreciated for our service, all of the above, or just dead.

Move to Canada, get a school deferment, or find bone spurs.

Our collective consciousness was somewhere between getting high, doing your duty, and trying to do some good.

Many of us did feel called to make some sort of stand, and we expressed optimism and idealism, guided by slogans like “Make War No More.” Others supported our country with an opposite optimism and idealism that the USA was good and right, and we should trust our government to stop the commies and save democracy and our way of life. But our enthusiasm for making the world a place of peace and love or preserving a way of life quickly became overshadowed by the need to feed, clothe, and shelter ourselves as we formed families and moved into adulthood. So we moved on. Or did we?

Some in my reunion class chatted like talking heads from Fox News. As white and Christian Americans, they claimed a birthright to have more, spend more, and concentrate on a good life for themselves. My suggestion that they were egregiously “entitled” was deemed un-American, and I suddenly had the feeling this was an old conversation.

Another classmate approached me and said, “You live in Africa? I have traveled, too. I went to Spain. How can those people live like that [in socialism]? How can you stand it?”

My answer: “I’m trying to help make it so the world works for everyone. I also have a good balance with travel, family stuff, and doing what I can … ”

But I was cut off by something about “those people” and a justification for indifference that ended with the statement, “I earned everything I have.” He walked away red-faced, and, again, I had the sense of old wounds. What happened to the idealism of the ’60s?

One answer might be simply the way we are wired. Our brains burn a lot of energy, and we are wired to conserve energy. So we tend to think about our immediate surroundings and short-term survival—not people 1,000 miles away or even 100 feet away if they’re from a different tribe, race, economic status, or perceived as no real threat. We will act instinctively to pull someone back from an oncoming car.

But what about similar crushing events we know about that are not so close or so immediate in distance—or in time? Whatever our spiritual beliefs about compassion and serving others, our DNA promotes self-serving inaction—and the discrepancy between belief and action makes us edgier and angrier. How much does what we see now reflect what we did or didn’t do then?

What do we do with this evil we see today? What should we expect from ourselves? Do we have any obligation to societies where feeding, educating, and immunizing their own is still just a hope?

Those questions are for each of us to mess with. What I do know is that Muhammad, Jesus, Moses, Buddha, and every other religious leader I can list was driven by thinking about how we live together in happiness, compassion, justice, and love.

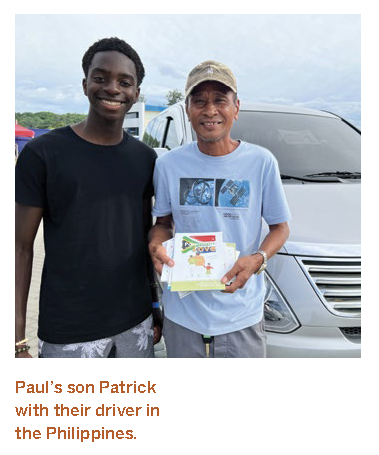

Yesterday, I was asked by the guy who drove us around an island in the Philippines if I was a Christian. I asked him what a Christian was. He smiled and asked me if we could take a picture together. My 10-year-old son took the photo. My sense is that the driver is also trying to seal the door where evil dwells.

Paul and his family left their home in the US to embark on a long trip through Asia on their way home to South Africa. He wrote this article on his way to Vietnam.

Click here for more about Spirituality & Health.