Optical Discomfort

Investing with a thoughtful, proactive, transparent process, as we do here at FIM Group, can be uncomfortable at times. This month, I’ll address some of the discomfort that can occur with our approach. I’ll also share some thoughts on why I feel that by accepting some of this discomfort along the way, our approach can lead to better long-term outcomes than alternative approaches like indexing. Sprinkled throughout the newsletter, you’ll find a number of exhibits. These describe some of the risk management tenets we consider and utilize when managing accounts.

Managing for Long-Term Success Rather than Short-Term Optics

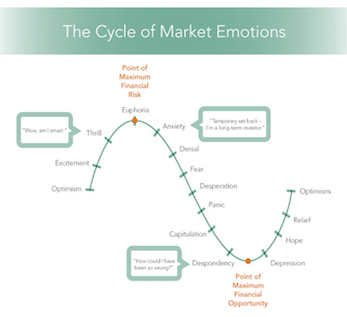

As FIM Group clients, you have the ability to see every portfolio action we take and, ultimately, the results of these actions, encompassing both the investments that work and those that don’t. We manage for long-term, inflation-beating and wealth-compounding returns. Every portfolio action we take is meant to accomplish this, which means we do not take action simply to improve portfolio statement “optics.” For example, we will not sell investments with unrealized losses just because they look like stinkers on our statements. In fact, at year-end, as others are doing just that and indiscriminately selling their under-performers, we often find exceptional buying opportunities.

“The three nomadic horsemen were riding through the Arabian Desert. It was late at night. A loud voice came from the sky and said, “Dismount!” Trembling, the men got off their horses. The voice then said, “Now fill your pockets with pebbles and stones and ride through the night. In the morning, when you open your pockets, you will be both happy and sad.” Quietly the men rode through the night. In the morning, they pulled out the contents of their pockets and were amazed to see that the pebbles and stones had turned to rubies, diamonds and other precious gems. They were happy to have such riches, but sad because in their fearful state they had not filled their pockets more.”

With this transparent approach to wealth management, it should be clear for clients who have been with us for any extended period of time that we make our fair share of mistakes. Some of these mistakes are in the form of realized losses where we either misjudge the quality of the business, pay too high a price or some combination of the two. This year, our investment in RCS Capital is heading down that path as an investment that can only be character-ized as a complete screw-up. We will also have investments where we are early in our purchase timing and have to sit through an extended period of unrealized losses before ultimately achieving the returns we expect. The small collection of natural resource investments we hold fall into this camp at the moment. And yes, we will also make investments that perform exceed-ingly well. But like the nomads in the story above, we will fail to allocate a big enough portfolio position to these and fully benefit from their success.

We own these mistakes, show them to you via our transparent reporting (via statements, newsletters, webinars, and one-on-one calls and meetings), and work hard as a team to learn from them. Despite the discomfort that these mistakes can bring, we still feel strongly that our proactive investment process, coupled with proactive financial planning and counseling (especially when markets get rocky as they inevitably do), are superior to alternatives like index investing.

Hiding Imperfections Doesn’t Eliminate Them

Remember that index investors essentially take an agnostic view to two important future performance factors: investment quality and investment price. Instead, these investors take an “own everything at any price” approach. Because such index funds appear on an investor statement as one simple line item, the optics can be quite different from those of a separate account like ours at FIM Group. For example, as I write this in mid-November, more than 25 stocks in the S&P 500 index fund are down more than 40% so far this year. Included in this list of stinker stocks are well-known companies like Chesapeake Energy, Alcoa, Whole Foods Market and Keurig Green Mountain. The optics of the simple investment statement provided by the index fund company (or adviser using such funds) may provide superficial comfort, but the reality is that such funds ALWAYS have their share of “duds.” Ironically, investors who choose U.S. stock market index funds for this perceived optical comfort, may actually be set up for significant levels of real discomfort when market conditions turn less benign. That’s because the lack of any real risk management deployed in these funds (beyond hyper-diversification) reveals itself when, as Buffett might say, “the tide goes out.”

The Discomfort of Being Out of Style

As noted above, our allocations to the clearly out of favor natural resources area have led to some unflattering line items on our monthly statements (showing current market values below our average cost for these holdings). More generally, our long-held philosophical bias to less flashy, reasonably priced “value” investments seems to have left us “out of style” this year compared to the “growth” strategies now in vogue. Such growth strategies typically emphasize the current pace of a company’s sales or earnings growth rather than the price investors are willing to pay for this growth (valuation). They target price appreciation rather than total return (price gains + dividends), and they emphasize potential value over current value. Stocks like Netflix and Amazon (which trade at more than 500x/300x expected 2015 earnings, respectively, compared to average S&P 500 stock of 16x) are representative poster children of the growth stock camp. Both of these and others in the social media and biotech sectors remind me of the Internet bubble conditions we saw in the 1990s.

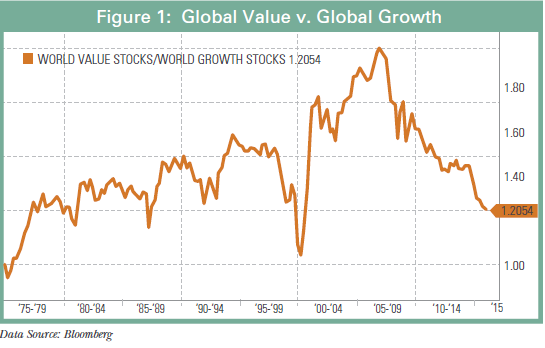

“Boring,” consistent dividend payers normally found in value investor portfolios with low price to cash flow or low price to book value ratios, in contrast, remain much less popular. As shown in Figure 1, value stocks have generally tended to outperform growth over long-term measurement periods. Along the way, though, value does have its “out-of-style” periods. For example, during most of the 1990s and especially in the late-1990s tech stock boom, value far underperformed growth. After a decade of strong value stock performance, growth has returned again as the popular place to be over the last few years. We do not expect value-oriented investments to lag their growth counterparts forever. Instead, we remain confident that the long-term trend of superior performance for value investments will eventually reassert itself as it’s done time and time again.

Risk Management

As is hopefully becoming clear in these comments, we believe that our job is to manage for long-term performance and not short-term optics. We could spend far fewer resources and take the easy route of index investing by ignoring investment quality and valuation factors and simply accepting whatever outcome the “market” delivers to us. While this might work in certain environments where market conditions are relatively benign (as they’ve been in the past few years of extraordinary monetary policy), we believe such a path can lead to very poor outcomes in more challenging markets. Over a full cycle of good times and bad, we believe that making informed decisions around investment quality and valuation can play important roles in minimizing permanent losses and, therefore, boosting our long-term odds of investment success. So rather than own everything, we choose to analyze companies, form investment theses and make investment decisions when we feel risk-adjusted expected returns justify doing so. We embrace global thinking and work hard to assess both investment-specific risks as well as the broader “macro” influences of things like taxes and inflation on our managed portfolios.

Taking a Pass on 15% Government Bond Yields

Speaking of inflation, I am writing this newsletter from Uganda, where official consumer price inflation has averaged nearly 10% annually over the last decade. Just a few years ago, Uganda inflation spiked to more than 30%! Here, short-term government notes guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the Uganda government yield in excess of 15%. Even at such high rates, the government has trouble selling them to finance its deficits. Why do they pay such high rates? First, Uganda is a dictatorship(ish) democracy with a long-history of relatively high inflation. Second, it is a very poor, land-locked country. Third, it is an election year and all the bad news is being washed up – corruption, cronyism, misspent aid, crazy priorities and such.

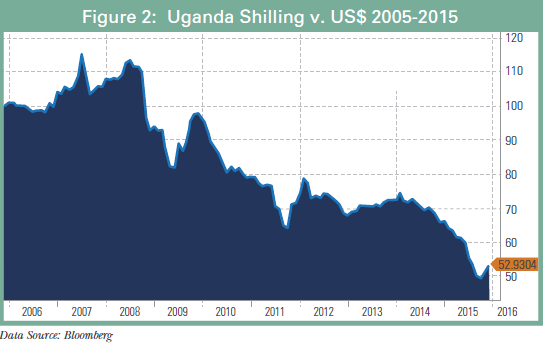

I recently had coffee with a local investment manager who manages a trust that only buys Uganda bonds. He said for the “average” Ugandan, getting 15%+ in the local currency is “very good” and feels good as they can watch their money compound quite quickly with little volatility, at least as measured in Uganda shillings. Of course, we know as international investors that Ugandan purchasing power is being eroded by taxes and inflation and that this manifests itself in currency depreciation. As Figure 2 shows, the Ugandan currency (the Uganda shilling) has lost around 50% of its value in US$ terms over the last decade. As it’s hard to see reasons for this currency depreciation trend to reverse, we won’t be investing in Uganda sovereign bonds anytime soon, despite their juicy yields.

Building Resilience Against the Inflation that No One Expects

Back in the U.S., the idea of a devalued dollar seems hard for many to fathom at the moment. We are now about five years into a strong dollar cycle, and it is natural to just extrapolate forward this trend for years to come, especially given what seems to be a policy divergence developing between the central banks of the U.S. (finally tightening policy?) and those in Europe and Japan (more loosening?). Those with gray hair can remember the talk of the U.S. dollar collapsing as it fell and inflation spiked in the 1970s and early 1980s. There were magazines and books at that time shouting their advice to buy gold, energy and real estate to protect against the “coming collapse.” The losers then were the fixed-income investors that saw their purchasing power erode due to taxes and inflation. This is just like the Uganda citizens who see their shilling accounts grow while their real wealth declines as taxes and inflation take their toll.

While markets globally don’t seem to reflect much worry, the massive amount of monetization that the U.S. is currently involved in, with deficit spending, ballooning expenses and such, could ultimately lead us to a period of inflation or currency weakness. This would be good for real estate, energy and companies that can adjust their business to stay profitable. While we do not expect inflation to return like it did years ago, we feel comforted that our portfolios are full of dividend-paying real estate, utility, and other “mission critical” product and service stocks that should be resilient if the current disinflation trend turns less benign. Our bond holdings are tilted toward those that have their interest rates tied to short-term rates or inflation. If rates rise, we anticipate a rising income stream from these investments. In the meantime, if inflation stays subdued (our expectation), we should see some price appreciation from these as investors, who have overreacted to Fed rate hike possibilities, realize that the world is not coming to an end.

Risk Managers First and Foremost

As risk managers first and foremost, we care most about protecting and growing real client wealth. We invest firm resources in order to make judgments related to investment quality and valuation, and we choose investments that we believe can be resilient to ever-evolving global economic, political, social and environmental trends. Our process is a transparent one, perhaps too transparent in that our realized and unrealized losses are there for all clients to see each month. We choose to keep it this way, knowing that there will times when the short-term “optics” don’t look so pretty. While I’d love to have every investment we make work out on the exact timing and level of total returns we expect, I know that isn’t realistic. Instead, we’ll make mistakes, we’ll own these mistakes and learn from them, and we’ll continue to obsess over the risk management factors that impact long-term returns.